Opulent Voice, our digital communications protocol, is used as the uplink for our open source satellite program Haifuraiya. Opulent Voice is also perfectly suited for terrestrial communications links.

Development so far has targeted the PlutoSDR. This platform has served us extremely well. However we’ve driven it as far as it can go. This is the story of how we learned we’d hit the wall, and what we did about it.

The long-term goal for Opulent Voice is an open source ASIC and world-class radio hardware. On the PlutoSDR, Opulent Voice data payloads are delivered from an external source to the modem’s network socket (USB). These data payloads have the Opulent Voice header, COBS header, UDP header, IP header, and if voice, RTP and OPUS headers. These data payloads arrive in the modem and are sent in to a transmit first in first out buffer (FIFO). The FIFO absorbs some of the network latency and uncertainties, so that we can support remote radio deployments as well as other challenging real-world timing situations.

The ARM Processor and FPGA in the PLUTO work together in order to send a preamble at the beginning of a transmission, randomize each data payload, apply forward error correction encoding to each data payload, interleave all the bits to take full advantage of the error correction, and then prepend a three-byte synchronization word to the beginning of each frame. The resulting 271 byte frame goes out over the air, modulated as a minimum shift keying signal.

Received signals are demodulated. Preambles help recover bit timing. The synchronization word is used to detect the start of the frame. The resulting payload is deinterleaved, the error correction is decoded, and then the resulting data is derandomized. We now have a data payload frame with Opulent Voice (and other) headers. This is delivered to the human-radio interface so that the data, voice, or text can be presented to the operator.

Up until the point where we fully integrated the forward error correction (FEC), the entire transceiver could fit into the Zynq 7010 in the PlutoSDR. This has 17,600 look-up tables (LUTs), a metric of what we call utilization on an FPGA. The number of LUTs available is similar to the number of shelves in a warehouse. If you fill up all the shelves, then there is no more room for inventory. However, that’s not the entire story. Filling up the LUTs with our logic is one aspect of FPGA utilization. Another aspect is how well the different parts of the design are connected together. Data flows through the design, and there are FPGA resources that must be used to make these connections. Some of the connections are only a bit wide, and some are 32 bits wide. The connection resources are like the aisles between the shelving systems in a warehouse. If you can’t reach a shelf, then it doesn’t matter if you have the inventory or not. Unreachable inventory is not useful.

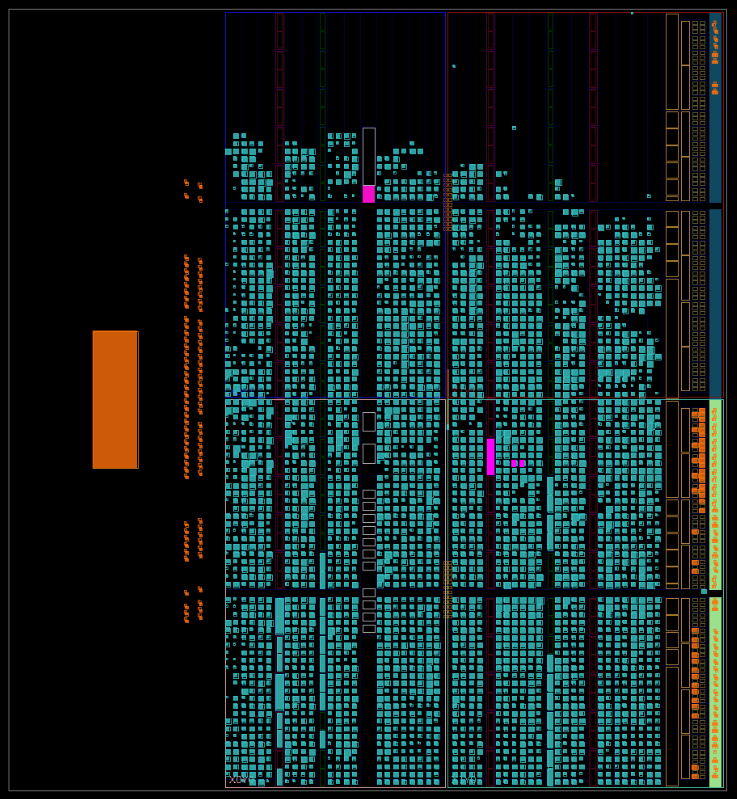

Below is a visualization of the FPGA utilization from Vivado. The cyan blocks are LUTs that are assigned. Blank spots in the upper 20% or so of the image are unassigned LUTs. Utilization immediately before complete FEC integration was approximately 60%. Why the difference between the visual 80% and the reported 60%? Because each cyan block in the image is not entirely full. What appears to be 80% utilization at this point in development was 60% by LUT count. This is what you want to see, with functions spread out over the resources and not densely packed in to smaller areas.

Radio functions at this point were good. Randomization, the FEC placeholder, and interleaving were all working. Frame sync word was being received and baseband data was being recovered. We expected to integrate “real” FEC and have it fit. There appeared to be enough resources. We decided to go for it.

We’d had a placeholder for the FEC in the design for a while. Since this was a rate 1/2 convolutional encoder, one bit in to the encoder resulted in two bits out. For the placeholder, we simply duplicated every bit and sent it on its way. Once we replaced this placeholder with the much more complicated real convolutional encoder and decoder, the utilization went over the resource limit. After a lot of work, we got it back down under the limit and it looked like that the design would still fit in the PlutoSDR’s relatively small Zynq 7010.

Or did it?

After carefully writing and testing in loopback an open source 1/2 rate constraint length 7 decoder depth 35 convolutional FEC (yes, the time-honored “NASA code”) we integrated the new code into the frame encoder and decoder in the source code. And, we went over budget. Not by much, but enough to where the design simply would not fit. After some work on reducing the generous allocation to the transmit and receive FIFO to get back some resources, we then came in under the LUT budget, but the failed routing. The next compromise was to drop back to a simpler interleaver. Interleavers reorder the bits in a frame in a way that spreads them out as widely apart from each other’s original position as possible. This makes the frame resilient against burst errors. This is a sudden crash of noise or interference or other dropout that lasts for a specific amount of time. The type of forward error correction that we were using wasn’t great against burst errors. If we got a burst error, then it would hurt us more than distributed errors. Distributed errors are the type of damage you get from low signal to noise ratios.Burst errors are like someone ripping out 40 pages of a novel you’re reading. That’s really annoying, but you can still finish the book. You just lose all that storyline. Now, if someone ripped out 40 pages from a book where the pages were all mixed up and not in sequential order, then you could put the pages back together in the right order and you’d just be missing a page every now and then. That’s easier to deal with because the damage is now spread out over the whole book. You can infer more of the storyline since contiguous pages were not affected.

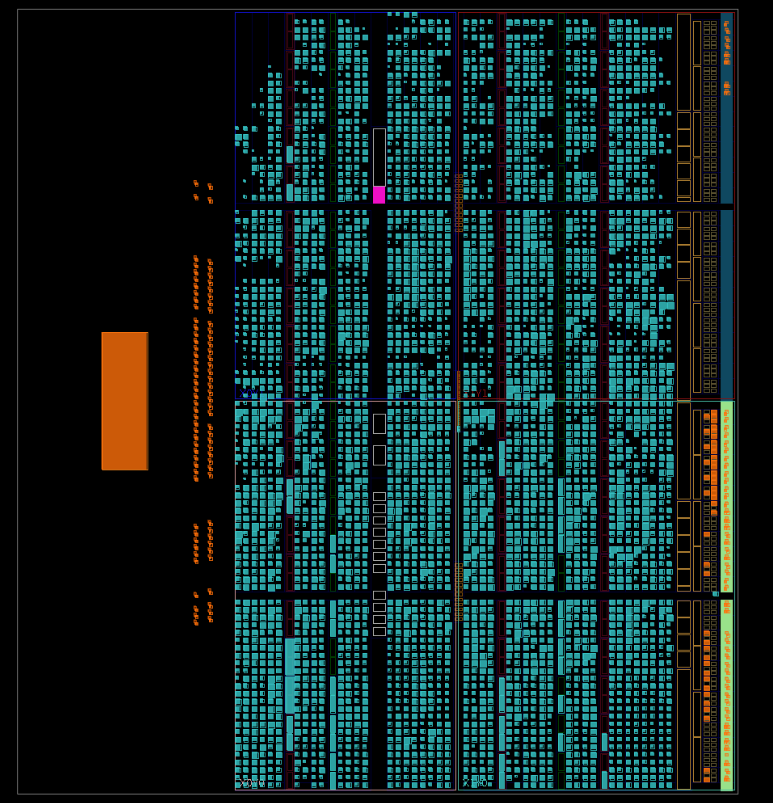

Now, imagine that instead of interleaving the pages before you leave your book lying around book vandals, that you interleaved all the paragraphs. Losing 40 pages worth of paragraphs is much less noticeable. Let’s keep thinking about this. How about interleaved sentences? Even better! Finally, let’s consider the best possible case. Interleaved letters. At this level of book defense, you can figure out almost every word in the book if you’re just missing a letter ever so often. This is how interleaving helps our forward error correction. Our FEC can deal really well with burst errors spread out, just like our brains can deal with missing letters spread out over a whole book. Unfortunately, our “interleave the letters” logic was too expensive. We had to drop back to something like “interleave the pages”. We had been interleaving each bit and enjoying the benefits. To reduce the size of the interleaver, we first simplified the design so that the buffer could be assigned to block RAM resources instead of LUTs. At one point this did get things under the LUT count, but it wouldn’t route the design. We had a full warehouse, but couldn’t reach all the shelves. Next, we changed the interleaver to re-order each byte, instead of each bit. This design required a simpler buffer and smaller lookup table for the positions. And, this new smaller design fit under the LUT count and routing worked again.

Utilization went down to 86%. We were thrilled. This was a huge step forward. We made a firmware build for the PlutoSDR and went into the lab to test over the air. However, the transmitter sent exactly one frame, and then quit. We called this bug “the transmitter stall” and started working on fixing it. The immediate blame fell on the encoder. We reasoned that this was probably a broken handshake between the data passing functions of the FIFO to the encoder, or the encoder to the deserializer. Not great, not terrible, just another thing to sort out. Simulation worked flawlessly, so the problem was only in hardware. Bypassing the encoder resulted in data flowing. It wasn’t being received, but the receiver was trying to decode unencoded data of the wrong size, so we didn’t think it was much of a clue.But, after combing through the code, and generating a lot of excellent bug fixes and other improvements, the transmitter stall stubbornly remained. Additional signals were brought out to status and control registers, so that we could get a little more visibility into the internals. Unlike in an FPGA simulator, we just can’t see most of the signals in the design in the PlutoSDR hardware. We can only see what’s exposed to the processor side through registers.We had recently gotten three new registers focused on the FIFO and frame synchronization. There was plenty of room in two of them, so we took over those bits to tell us what the encoder was up to. And then it got very interesting. The patterns that we were seeing clearly showed a stall. But, not in the forward error correction, which was the new code and therefore getting the suspicion. Instead, the stall was in the interleaver.

The real bug was in the loop for the interleaver. An Opulent Voice data payload has 134 bytes. A forward error corrected data payload has 268 bytes. But, the interleaver was only reordering 134 of the 268 bytes. This was an easy fix, only one line of code. But that one line of code caused utilization to soar above the LUT limit again. This was very curious.

And then the real learning started. The process of turning source code into FPGA hardware involves a process called synthesis. Synthesis figures out how to represent your source code into logic gates. Synthesis is followed by implementation, where we place and route the design in particular hardware targets. Synthesis can and will optimize parts of your design away. Synthesis will remove dead or unreachable code. And, only doing 134 of 268 things in your interleaver will remove quite a bit of unused unreachable code.

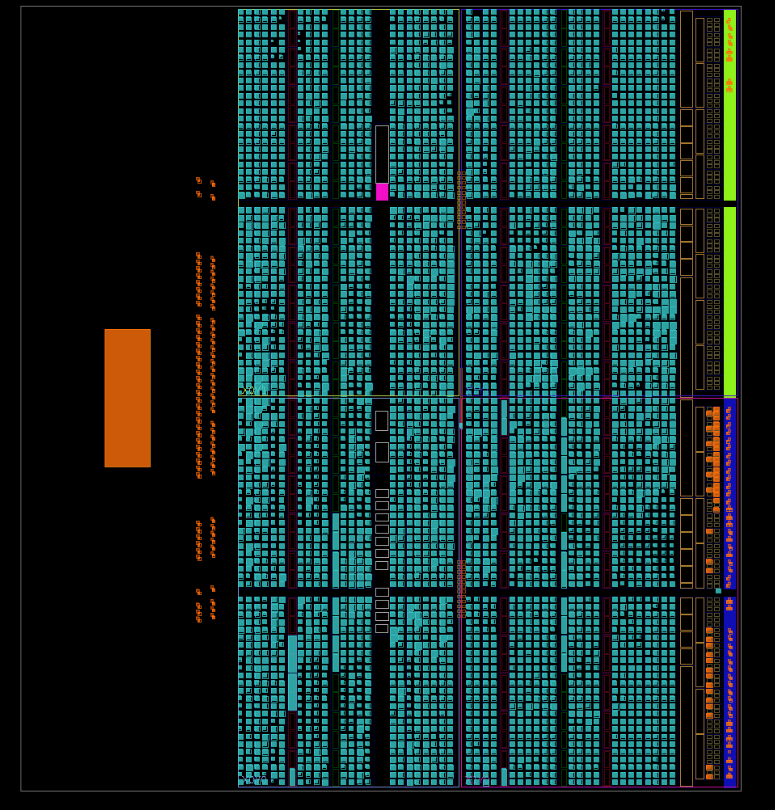

Once this became clear, we dug in harder into the design. We knew we had a tricky situation with the pseudo random binary sequencer (PRBS) tricking the synthesizer into not bothering to implement the encoder. We’d already protected the encoder with “don’t touch” attributes that told the synthesizer to keep its ambitious little hands off our code. But, we didn’t protect the separate module for the “real” FEC. And, we hadn’t protected the decoder either. And, now we had this much larger loop in the interleaver. We got to work protecting the design against the optimizer, and then doing a lot of optimizing ourselves in order to free up more resources. After properly protecting all the new code, which implemented all the missing parts of the encoder and the decoder, we now also had more logic in the design from the proper loop sizing. We removed the (unused) TDD function, I2C peripheral, and SPI peripheral. We simplified anything we could think of that was a buffer. We thought about removing PRBS entirely, but the savings were minimal. For a brief moment, we got under the LUT limit. Here’s what that looked like.

It looked like we’d succeeded. But, the table of utilization results broke the bad news. We’d protected the frame encoder, the FEC encoder, and the frame decoder, but the synthesizer had still removed most of the internals from the FEC decoder. It looked good from the top level, but it was missing vital functions deep inside. Protecting all the signals in the decoder busted our LUT limit hard. There was nothing else to remove without cutting deeply into the quality of the design. We were already settling for hard (instead of soft) decisions in the frame sync word detector and FEC, and we were already running with a compromised byte-level interleaver. We still had symbol lock to integrate, and we didn’t want to rewrite the entire design just to fit this one hardware development target.

It was time to move to a different development target. This process of changing from a platform you’ve outgrown to another with better resources is much like abandoning a sinking ship. You really don’t want to jump into the freezing cold ocean unless you can see the lifeboats coming from the other ship. But, we knew this day was coming, and we were prepared.