Porting the Opulent Voice MSK modem from PlutoSDR to LibreSDR hit a hard wall. The PlutoSDR uses a different digital interface internally than the LibreSDR. Part of this new interface (LVDS) is a tuning algorithm. The tuning is needed to get the interface timing calibrated. The transmission tuning algorithm failed consistently during boot. This transmission tuning algorithm doesn’t tune the RF transmitter, but refers to how the transmit data from the radio chip is sent out over the bus to the FPGA. Usually, tuning algorithm information is sent to the next block down in the reference diagram, and that block knows how to participate in this tuning algorithm. However, we cut those wires and “soldered in” our own components. We don’t do any of this tuning algorithm. What we have done is take over the timing for the radio within our logic. We can handle it, but the radio chip doesn’t know this!

The tuning diagnostic showed all failures across the entire timing grid. Here’s what it looked like in the logs:

SAMPL CLK: 61440000 tuning:

TX 0:1:2:3:4:5:6:7:8:9:ac:d:e:f:

0:# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #

1:# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #

ad9361 spi0.0: ad9361_dig_tune_delay:

Tuning TX FAILED!

This pattern indicates a fundamental problem with the timing not happening at all, and not marginal timing. The system worked fine on PlutoSDR. Stock LibreSDR firmware booted without issues. What was different? Well, the presence of our design was different. But, how could hardware working perfectly on another platform, and working perfectly in simulation, cause this sort of a failure?

The key insight came from comparing Pluto and LibreSDR at the hardware interface level. Pluto uses a CMOS digital interface to the AD9361 radio chip. No timing calibration needed. LibreSDR uses LVDS, which requires precise timing calibration between FPGA and AD9361. The driver’s tuning algorithm sends test patterns through the transmit path and checks what comes back on the feedback clock.

Here’s where our MSK circuits caused the problem. In our FPGA design, the MSK modulator sits directly in the TX data path. During kernel boot, before any userspace initialization, MSK outputs zeros. The tuning algorithm expects to see its test patterns reflected back. Instead, it sees nothing but zeros at every timing setting. Every cell fails. Stock LibreSDR firmware passes tuning because its FPGA design has a clean path from the internal DDS to the DAC during boot.The AD9361 driver supports a digital-interface-tune-skip-mode device tree property. That’s a fancy way of saying that we have choices for how the driver does these tests. There’s a setting that can be 0, 1, 2, or 3.

0 = Tune both RX and TX

1 = Skip RX tuning

2 = Skip TX tuning

3 = Skip both

Setting skip-mode to 2 tells the driver “Don’t try to calibrate TX timing because the FPGA handles it.” This looked like what would be most correct for our design. MSK owns the transmit data path, and our FPGA timing constraints were already met with 0.932 ns of “slack”, or timing margin. RX tuning still runs normally because MSK sits downstream of where this test occurs on the receive path.

The fix was a one-line change in ori/libre/linux-dts/zynq-libre.dtsi. Here’s that change!

adi,digital-interface-tune-skip-mode = <2>; /* Skip TX tuning - MSK owns TX path */

This one line removed the block and we were able to boot and confirm transmission over the air. This revealed yet more very interesting problems that will be described in next month’s newsletter.

While debugging the boot issue, we discovered the build system was generating a Pluto-centric uEnv.txt that lacked SD card boot support for LibreSDR. We had to manually swap in the uEnv.txt file to get it to boot off the SD card. This wasn’t going to work long-term, so we updated the Makefile. It now automatically adds the sdboot command for SD card booting and fixes the serial port address (serial@e0001000 to serial@e0000000). These fixes apply only when PLATFORM=libre, keeping Pluto builds unchanged.

With these changes, LibreSDR booted successfully with the MSK modem. We confirmed TX/RX state machine registers responding via libiio, RSSI register readable (custom MSK logic working), frame sync status visible, RF transmission confirmed on spectrum analyzer, and the 61.44 MHz sample clock verified. This was a huge step forward, and gave us valuable experience in porting our design to different FPGAs. We expect to port the design to the zcu102 development board (with Ultrascale+ FPGA) in order to demonstrate Haifuraiya HEO/GEO satellite work in 2026. The port process, in order for Opulent Voice to be in the uplink receiver channel bank, will go very similar to what is described here.

In Remote Labs today, we’re now debugging actual MSK modem behavior (frame timing and synchronization) rather than fighting boot failures. This represents a significant milestone: the first successful integration of the Opulent Voice FPGA design with LibreSDR hardware.

Lessons learned? CMOS vs LVDS interfaces have different boot-time requirements that aren’t obvious until you hit them. When custom FPGA logic sits in the data path, driver auto-calibration may not work as expected. Device tree properties can tell drivers “I know what I’m doing” when appropriate. Build system automation prevents manual copy errors that waste debugging time.

Next steps? Debug the weird 9.42-frame gap appearing after dummy frames. Investigate frame synchronization timing. Loopback testing to verify full transmit and receive chain. And, integration testing with Dialogus and Interlocutor.

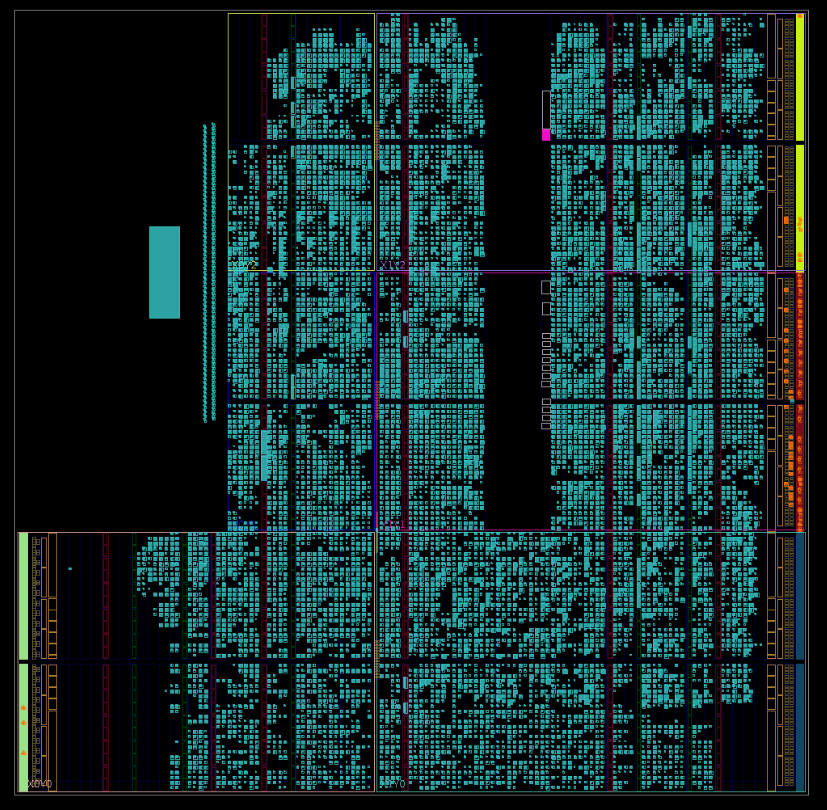

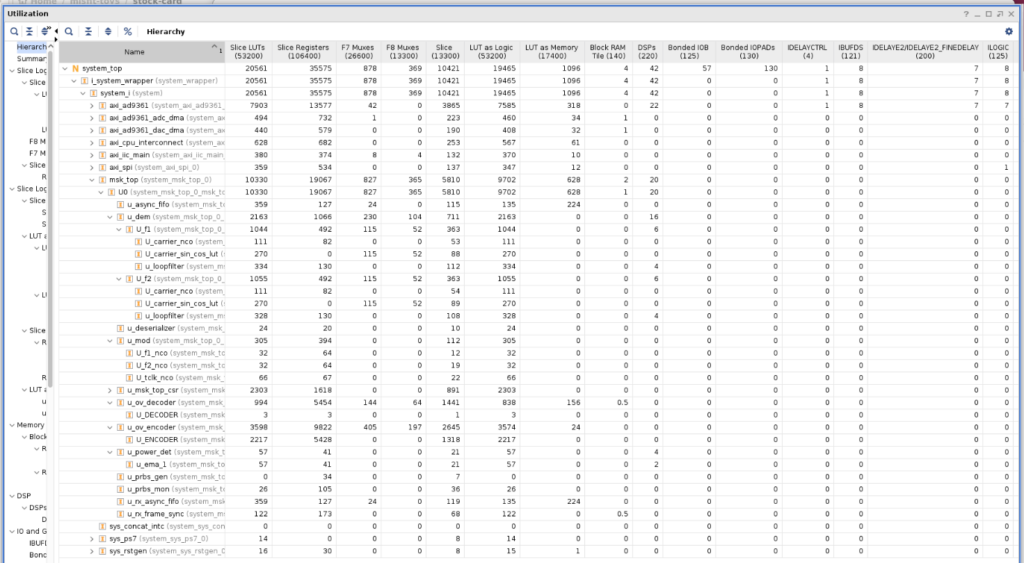

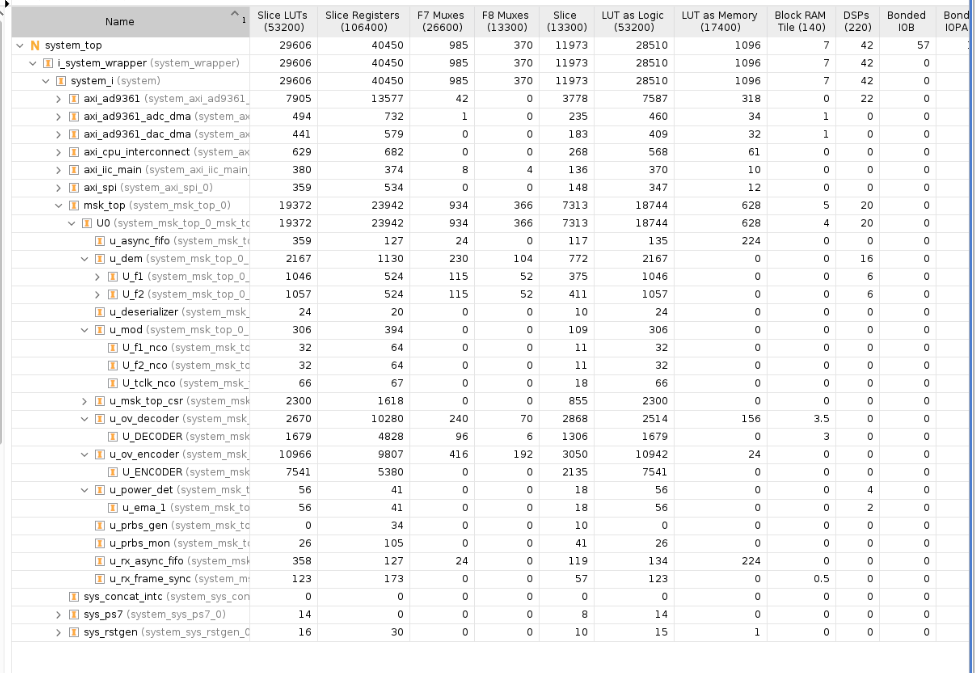

Finally, we could close the circle. We had to abandon the PlutoSDR because we ran out of room on the FPGA. What did the FPGA utilization look like now on the LIbreSDR?

Well, that’s a lot better! The design has a different shape because of the different layout of the programmable logic. And, there’s more room. But wait. There’s something wrong.

Look at the decoder utilization. Only 3 logic units? That’s not even remotely plausible. The Viterbi decoder had been completely optimized out! Our decoder is a hollow shell, just passing data from derandomizer to deinterleaver.

Aggressively adding instructions to the synthesis tool reversed the damage. Carefully inspecting the log files for any disconnections or removed logic, and protecting any signals affected anywhere in our design, finally resulted in a completely clean bill of health. Utilization reports were run again, and the true picture of how much logic it takes to place and route our design came into focus.

With hard decision Viterbi decoder and a hard decision synchronization word detector, we are at 56% utilization. We now have plenty of room to go back to the bit-level interleaver, upgrade to a soft decision decoder, and get a true correlator for the synch word detector. This is a very satisfying result and gives us a truly good place to be for 2026.