This article documents the process of upgrading a working hard-decision Viterbi decoder to soft-decision decoding in an FPGA-based MSK modem implementing the Opulent Voice protocol. Soft-decision decoding provides approximately 2-3 dB of coding gain over hard-decision, which is significant for satellite communications and weak signal work where every dB matters. We describe the architectural changes, the bugs encountered, and the systematic debugging approach used to resolve them.

Introduction

The Opulent Voice (OPV) protocol uses a rate 1/2, constraint length 7 convolutional code with generator polynomials G1=171 and G2=133 in octal representation. The original implementation used hard-decision Viterbi decoding, where each received bit is quantized to 0 or 1 before decoding. Soft-decision decoding preserves additional information from the demodulator. In addition to the output of a 0 or a 1, we also have what we are going to call “confidence information” from the demodulator. This additional information allows us to make better decisions because some bits are more reliable than others. Some bits come in strong and clear and others are very noisy. If we knew how sure we were about whether the bit was a 0 or a 1, then we could improve our final answers on what we thought was sent to us. How is this improvement achieved? We can’t read the mind of the transmitter, so where does this “confidence information” come frome? How do we use it?

Consider receiving two bits. We get one bit with a strong signal and we get the other bit near the noise floor. Hard decision treats both bits equally. They’re either 0 or 1, case closed. Soft decision decoding says “I’m 95% confident this first bit is a 1, but only 55% confident about the second bit being a 0.” When the decoder must choose between competing paths, it can weight reliable bits more heavily than the ones it has less confidence about.

When our modem demodulates a bit, the result is calculated as a signed 16 bit number. For hard decisions, we just take the sign bit from this number. This is the bit that tells us if the number is positive or negative. Negative numbers are interpreted as 1 and positive numbers are interpreted as 0. The rest of the number, for hard decisions, is thrown away. However, we are going to use the rest of the calculation for soft decisions. How close to full scale 1 or 0 was the rest of the number? This is our confidence information.

In practice, a technique called 3-bit soft quantization captures most of the available information and gets us the answers we are after. Quantization means that we translate our 16 bit number, which represents a very high resolution of 65536 levels of confidence, into a 3 bit number, which represents a more manageable 8 levels of confidence. Think of this like when someone asks you to rate a restaurant on a scale from 1 to 5. That’s relatively easy. 1 is terrible. 5 is great. 3 is average, or middle of the road. If you were asked to rate a restaurant on a scale from 1 to 65536, you probably could, but how many levels of quality are there really? Simplifying a rating to a smaller number of steps makes it easier to deal with and communitcate to others. This is what we are doing with our 16 bit calculation. Converting it to a 3 bit calcuation simplifies our design by quite a bit without sacrificing a lot of performance. We can always go back to the 16 bit number if we have to. Since we were using signed binary representation, 000 is the biggest number and 111 is the smallest. If we print the numbers out, you can see how it works if we just take the sign bit and “round up” or “round down” the rest of the result.

Here’s our quantized demodulator output. The sign of the number (positive or negative) is the first binary digit. Then the rest of the number follows.

000 largest positive number - definitely received a 0

001 probably a 0

010 might be a 0

011 close to zero, but still positive

100 close to zero, but still negative

101 might be a 1

110 probably a 1

111 smallest negative number - definitely received a 1

After the conversion, our implementation uses the following rubric.

confidence outcome

000 strong ‘0’ (high positive correlation)

111 strong ‘1’ (high negative correlation)

011-100 uncertain!

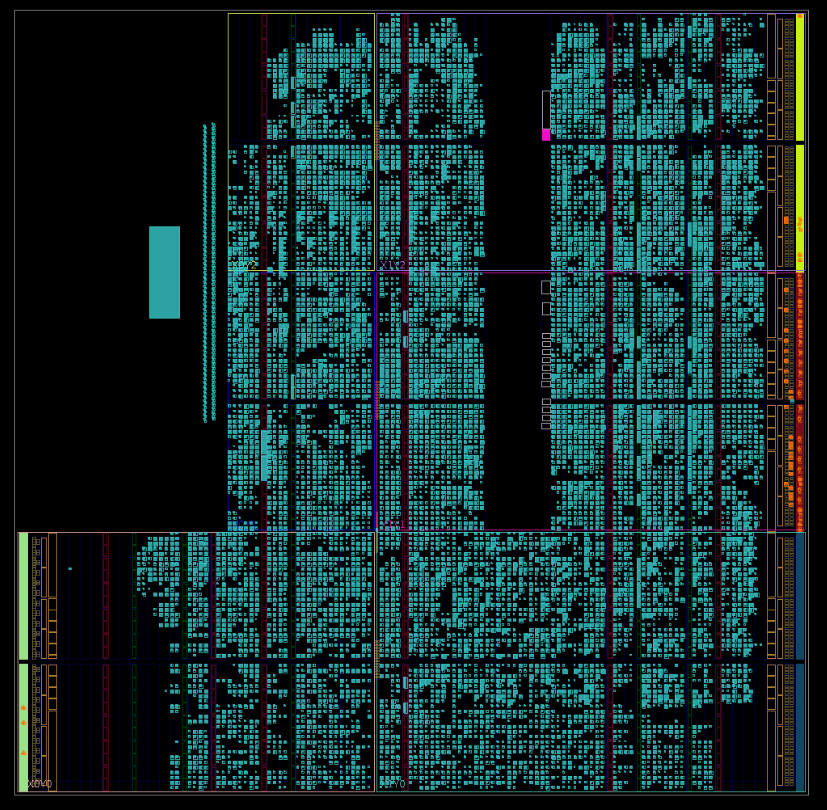

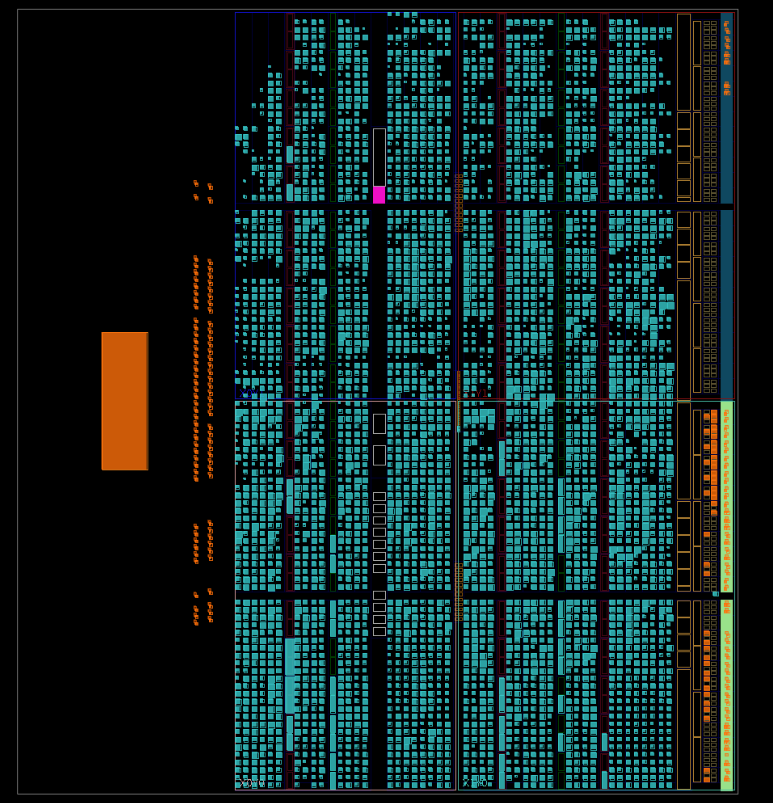

System Architecture

Original Hard-Decision Path

[Demodulator] to [Frame Sync] to [Frame Decoder] to [Output]

| |

rx_bit Deinterleave

rx_valid Hard Decision Viterbi

Derandomize

The hard-decision path is as follows. The demodulator outputs `rx_bit` (0 or 1) and an `rx_valid` strobe. This strobe tells us when the `rx_bit` is worth looking at. We don’t want to pick up the wrong order, or get something out of the oven too early (still frozen) or too late (oops it’s burned). `rx_valid` tells us when it’s “just right”. The frame sync detector finds sync words in the incoming received bitstream and then assembles bytes into frames. The sync word is then thrown away, having done its job. The resulting frame needs to be deinterleaved, to put the bits back in the right order, and then we do our forward error correction. After that, we derandomize. We now have a received data frame.

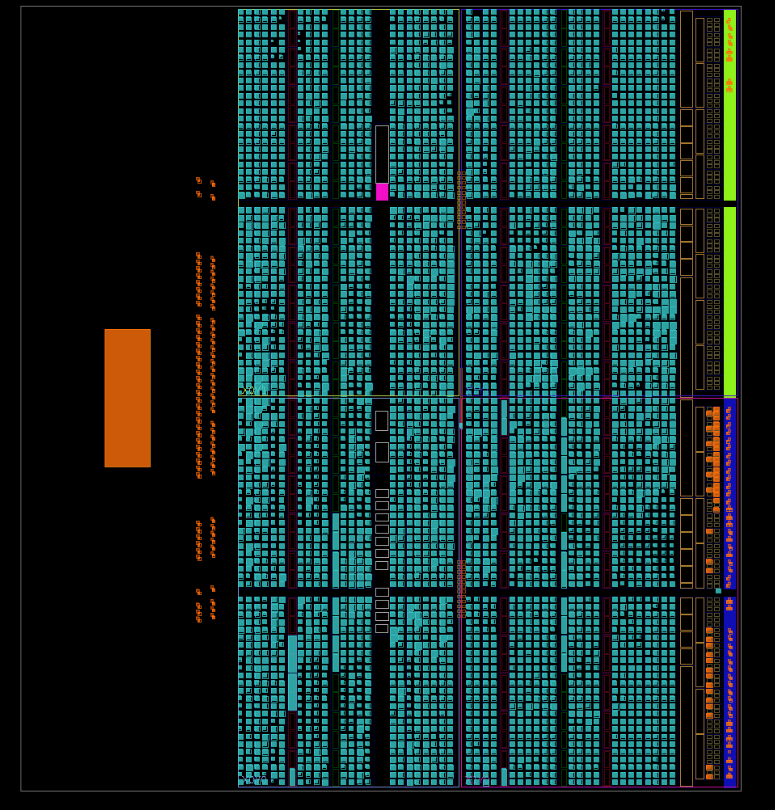

New Soft-Decision Path

[Demodulator] to [Frame Sync Soft] to [Frame Decoder Soft] to [Output]

| |

rx_bit Deinterleave

rx_valid Soft Decision Viterbi

rx_soft[15:0] Derandomize

|

Quantize to 3-bit

Store soft buffer

There is a lot here that is the same. We deinterleave, decode, and derandomize. We decode with a new soft decision Viterbi decoder, but the flow in the soft frame decoder is essentially the same as in the hard decision version.

What is new is that the demodulator provides 16-bit signed soft metric alongside the previously provided hard bit. This is just bringing out the “rest” of the calculation used to get us the hard bit in the first place. A really nice thing about our radio design is that this data was there all along. We didn’t have to change the demodulator in order to use it.

Another update is that the frame sync detector quantizes and buffers these soft “confidence information” values. So, we have an additional buffer involved. Finally, the frame decoder uses soft Viterbi with separate G1/G2 soft inputs, instead of the `rx_bit` that we were using before.

Implementation Details

Soft Value Quantization

The demodulator’s soft output is the difference between correlator outputs: `data_f1_sum – data_f2_sum`. Large positive values indicate confident ‘0’, large negative indicate confident ‘1’.

FUNCTION quantize_soft(soft : signed(15 DOWNTO 0)) RETURN std_logic_vector IS

BEGIN

-- POLARITY: negative soft = ‘1’ bit, positive soft = ‘0’ bit

IF soft < -300 THEN

RETURN “111”; -- Strong ‘1’ (large negative soft)

ELSIF soft < -150 THEN

RETURN “101”; -- Medium ‘1’

ELSIF soft < -50 THEN

RETURN “100”; -- Weak ‘1’

ELSIF soft < 50 THEN

RETURN “011”; -- Erasure/uncertain

ELSIF soft < 150 THEN

RETURN “010”; -- Weak ‘0’

ELSIF soft < 300 THEN

RETURN “001”; -- Medium ‘0’

ELSE

RETURN “000”; -- Strong ‘0’ (large positive soft)

END IF;

END FUNCTION;

The thresholds (+/- 50, +/- 150, +/- 300) must be calibrated for the specific demodulator. If you want to implement our code in your project, then start with these values and adjust based on observed soft value distributions.

Soft Buffer Architecture

The Opulent Voice frame contains 2144 encoded bits (134 payload bytes × 8 bits × 2 for rate-1/2 error correcting code). Each bit needs a 3-bit soft value, requiring 6432 bits of storage.

TYPE soft_frame_buffer_t IS ARRAY(0 TO 2143) OF std_logic_vector(2 DOWNTO 0);

SIGNAL soft_frame_buffer : soft_frame_buffer_t;

Bit Ordering Challenges

The most subtle bugs in getting this design to work involved bit ordering mismatches between hard and soft paths. The system has multiple bit-ordering conventions that must align. There were several bugs that tripped us up in this category. The way to solve it was to carefully check the waveforms and repeatedly check assumptions about indexing.

Byte transmission: MSB-first (bit 7 transmitted before bit 0)

Byte assembly in receiver: Shift register fills MSB first

Interleaver: 67×32 matrix, column-major order

Soft buffer indexing: Must match hard bit indexing

The Arrival Order Problem

Bytes transmit MSB-first, meaning for byte N a `bit_count` of 0 receives byte(7) = interleaved[N×8 + 7] and a `bit_count` of 7 receives byte(0) = interleaved[N×8 + 0]

The hard path naturally handles this through shift register assembly. The soft path must explicitly account for it. We got this wrong at first and had to sort it out carefully.

Wrong approach which caused bugs:

-- Tried to match input_bits ordering with complex formula

soft_frame_buffer(frame_byte_count * 8 + (7 - bit_count)) <= quantize_soft(...);

This formula has a timing bug: `bit_count` is read before it updates (VHDL signal semantics), causing off-by-one errors.

Correct approach which gave the right results:

-- Store in arrival order, handle reordering in decoder

soft_frame_buffer(frame_soft_idx) <= quantize_soft(s_axis_soft_tdata);

frame_soft_idx <= frame_soft_idx + 1;

Then in the decoder, we used a combined deinterleave+reorder function:

FUNCTION soft_deinterleave_address(deint_idx : NATURAL) RETURN NATURAL IS

VARIABLE interleaved_pos : NATURAL;

VARIABLE byte_num : NATURAL;

VARIABLE bit_in_byte : NATURAL;

BEGIN

-- Find which interleaved position has the deinterleaved bit

interleaved_pos := interleave_address_bit(deint_idx);

-- Convert interleaved position to arrival position (MSB-first correction)

byte_num := interleaved_pos / 8;

bit_in_byte := interleaved_pos MOD 8;

RETURN byte_num * 8 + (7 - bit_in_byte);

END FUNCTION;

Soft Viterbi Decoder

The soft Viterbi decoder computes branch metrics differently than hard Viterbi decoders. Hard-decision branch metric has a Hamming distance of 0, 1, or 2.

branch_metric := (g1_received XOR g1_expected) + (g2_received XOR g2_expected);

Soft-decision branch metric is the sum of soft confidences.

-- For expected bit = ‘1’: metric = soft_value (high if received ‘1’)

-- For expected bit = ‘0’: metric = 7 - soft_value (high if received ‘0’)

IF g1_expected = ‘1’ THEN

bm := bm + unsigned(g1_soft);

ELSE

bm := bm + (7 - unsigned(g1_soft));

END IF;

-- Same for G2

The path with the highest cumulative metric wins. This is the opposite convention from hard-decision Hamming distance, where the least differences between two different possible patterns wins.

Debugging Journal

Bug #1: Quantization Thresholds

Symptom was all soft values were 7 (strong ‘1’). But, we knew our data was about half 0 and about half 1. The root cause was that initial thresholds (+/- 12000) were far outside the actual soft value range (+/- 400). We adjusted thresholds to +/- 300, +/- 150, and +/- 50.

Lesson? Always check actual signal ranges before setting thresholds.

Bug #2: Polarity Inversion

Symptom was that output frames were bit-inverted. The root cause was that soft value polarity convention was backwards?positive was mapped to ‘1’ instead of ‘0’. This was fixed by inverting the quantization mapping.

Bug #3: Viterbi Output Bit Ordering

The symptom was that decoded bytes had reversed bit order. Viterbi traceback produces bits in a specific order that wasn’t matched during byte packing. After several missed guesses, we corrected the bit-to-byte packing loop.

FOR i IN 0 TO PAYLOAD_BYTES - 1 LOOP

FOR j IN 0 TO 7 LOOP

fec_decoded_buffer(i)(j) <= decoder_output_buf(PAYLOAD_BYTES*8 - 1 - i*8 - j);

END LOOP;

END LOOP;

Bug #4: VHDL Timing – Stale G1/G2 Data

The symptom was that the first decoded bytes were correct, and the rest were garbage. This was super annoying. The root cause was that `decoder_start` was asserted in the same clock cycle as G1/G2 packing, but VHDL signal assignments don’t take effect until process end. We added pipeline stage. We pack G1/G2 in `PREP_FEC_DECODE`, assert start, and wait for `decoder_busy` before transitioning to `FEC_DECODE`

Bug #5: Vivado Optimization Removing Signals

In Vivado’s waveform visualizer, the `deinterleaved_soft` array was partially uninitialized in simulation. The cause was unclear, but we surmised that Vivado optimized away signals it deemed unnecessary.

We added `dont_touch` and `ram_style` attributes. This seemed to fix the symptom, but we didn’t feel like it was a cure.

ATTRIBUTE ram_style : STRING;

ATTRIBUTE ram_style OF soft_buffer : SIGNAL IS “block”;

ATTRIBUTE dont_touch : STRING;

ATTRIBUTE dont_touch OF soft_buffer : SIGNAL IS “true”;

Bug #6: Soft Buffer Index Timing

We saw that soft values were stored at wrong indices. The entire pattern was shifted. Storage formula `byte*8 + (7 – bit_count)` read `bit_count` before increment, which pulled everything off by one. Waveform showed index 405 being written when 404 was expected. The formula was mathematically correct, but VHDL signal assignment semantics meant `bit_count` had its old value.

We abandoned the complex indexing formula. We now store in arrival order using simple incrementing counter and handle reordering in decoder.

Bug #7: Wrong Randomizer Sequence

Output frames were completely corrupted despite all other signals appearing correct. The cause was that the soft decoder was created with a different randomizer lookup table than the encoder and hard decoder.

Encoder/Hard Decoder: `x”A3”, x”81”, x”5C”, x”C4”, …`

Soft Decoder (wrong): `x”96”, x”83”, x”3F”, x”5B”, …`

When creating the soft decoder, the randomizer table was generated incorrectly instead of being copied from the working hard decoder. We copied exact randomizer sequence from `ov_frame_decoder.vhd`, and it started working. Lesson learned? When creating a new module based on an existing one, copy constants exactly. Don’t regenerate them.

Debugging Methodology

Systematic Signal Tracing

When output is wrong, work backwards from output to input. Check final output values. Check intermediate values after major transformations (after derandomize, after Viterbi, after deinterleave). Check input values to each stage, even if you totally believe you’re getting the right data. Find where expected and actual diverge. Don’t try to solve “in the middle” of wrongness. Work on finding the edges between correct and incorrect, even if it points in unexpected directions.

Reference Implementation

Maintain a reference design. This independent design needs to be different than the platform and language that you are working on. This reference performs identical operations and can help you figure things out. For example, our Python references helped us solve problems in our VHDL.

def convolutional_encode(input_bits):

G1, G2 = 0o171, 0o133

shift_reg = 0

output = []

for bit in input_bits:

shift_reg = ((shift_reg << 1) | bit) & 0x7F

g1_bit = bin(shift_reg & G1).count(‘1’) % 2

g2_bit = bin(shift_reg & G2).count(‘1’) % 2

output.extend([g1_bit, g2_bit])

return output

def interleave(bits):

ROWS, COLS = 67, 32

interleaved = [0] * len(bits)

for i in range(len(bits)):

row, col = i // COLS, i % COLS

interleaved[col * ROWS + row] = bits[i]

return interleaved

Compare FPGA signals against reference at each stage.

Test Patterns

Use recognizable patterns that make errors obvious. For example, we use alternating frames for our test payload data. First frame is sequential. The bytes go 0x00, 0x01, 0x02, and so on up to 0x85. The second frame is offset from this. 0x80, 0x81, 0x82, up to 0xFF where it rolls over to 0x00, 0x01, 0x02,0x03, 0x04 ending at 0x05. Alternating distinctive frames like these help to reveal a wide variety of errors. Frame boundary issues, such as when a frame starts in the middle of another frame, can be spotted. Initialization issues might be revealed as the root cause if only first frame works and all the rest fail. And, state machine issues could be the underlying problem if the pattern of output bytes is inconsistent.

Waveform Analysis Tips

Check before clock edge! Signal values are sampled at rising edge. What you see “after” may be the next value, not the current value. Watch for ‘U’ (uninitialized). This indicates a signal never written or it got optimized away. Why wasn’t it ever written? Why is it missing? This is a clue! Track indices. When storing to arrays, verify both the index and value are correct. Off by one errors are very common. Compare parallel paths. If, for example, a hard decision path works but soft decisions do not, the difference reveals the bug.

Results

After fixing all bugs, the soft-decision decoder produces identical output to the hard-decision decoder for clean signals. The benefit appears at low SNR where soft decisions allow the Viterbi algorithm to make better path selections. Soft decisions add 2-3 additional dB of coding gain over hard decisions, which brought us 5 dB of coding gain.

Conclusions

Upgrading from hard to soft decision decoding requires careful attention to bit ordering, VHDL timing, polarity conventions, and code re-use. Multiple conventions must align. You have to get transmission order, assembly order, interleaver order, and buffer indexing all correct. Signal vs. variable semantics matter for single-cycle operations. This is a language-specific thing for VHDL, but all languages have crucial differences between the tools used to get things done in code. Document and verify positive/negative soft value meanings. In other words, pick heads or tails and stick with it. Copy constants and lookup tables exactly from working code. Re-use saves time until a copy and paste error slows the debugging process for hours or days.

The 2-3 dB coding gain from soft decisions is worth the implementation complexity for satellite communications where link margins are precious. The coding gain helps in terrestrial settings to increase range and reliability.

Source Code

The complete implementation is available in the Open Research Institute `pluto_msk` repository at `https://github.com/OpenResearchInstitute/pluto_msk`. `frame_sync_detector_soft.vhd` is the frame sync with soft value quantization and buffering. `ov_frame_decoder_soft.vhd` is the frame decoder with soft Viterbi. And `viterbi_decoder_k7_soft.vhd` is the soft-decision Viterbi decoder core. These are separate files from the hard decision versions, which are also available. Look for files without the soft in the titles. This work may still be in the encoder-dev branch when you read this, but the eventual destination is main.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed at Open Research Institute as part of the Opulent Voice digital voice protocol development. It is open source and is publised under CERN open hardware licesnse version 2.0. Special thanks to Paul Williamson KB5MU for Remote Labs hardware support and testing, Matthew Wishek NB0X for modem architecture, design, and implementation, and Evariste F5OEO for integration advice for the Libre SDR. Thank you to the many volunteers reviewing the work and providing encouragement and support during the debugging process.